Inflation Decline – What It Means and Why It Matters

When we talk about inflation decline, a sustained reduction in the rate at which prices increase, often measured by key price indexes. Also known as deflationary pressure, it signals a shift in the economy that can affect everything from groceries to mortgages. inflation decline has been a hot topic across Africa as households feel the pinch of past price spikes and policymakers scramble to keep growth steady.

Key Factors Behind the Turn‑around

One of the most direct ways to gauge a drop in inflation is by looking at the Consumer Price Index, the basket‑of‑goods measure that tracks price changes for everyday items. When the CPI slows, it usually means lower headline inflation. In many African nations, recent CPI reports show a modest easing after years of double‑digit gains. A major driver behind that easing is monetary policy, the set of actions by central banks to control money supply and interest rates. Central banks have tightened rates, curbed excess liquidity, and in some cases, let exchange rates stabilize, all of which cool demand and push prices down. This relationship creates a semantic triple: Inflation decline requires prudent monetary policy, and monetary policy influences the consumer price index.

Another piece of the puzzle is interest rates, the cost of borrowing set by central banks that affects loans, mortgages, and business financing. Higher rates make credit more expensive, which dampens spending and slows price growth. As rates rise, many consumers see smaller jumps in grocery bills, but they also feel the squeeze on loan repayments. This trade‑off directly ties into purchasing power, the amount of goods and services a unit of currency can buy. When inflation declines, purchasing power can improve if wages keep up, but if wage growth stalls, the real benefit may be limited. In short, inflation decline enhances purchasing power, provided income levels hold steady.

Across the continent, the impact of these forces varies. In South Africa, the Reserve Bank’s aggressive rate hikes have already turned the inflation curve down, giving consumers a brief respite at the checkout. Kenya’s central bank, meanwhile, balances tight policy with food‑security concerns, because a sharp slowdown could hurt smallholder incomes. Nigeria, still wrestling with high food prices, sees a slower CPI drop but remains vigilant about fiscal deficits. These country‑specific snapshots illustrate how inflation decline isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all story; each economy mixes monetary policy, interest rates, and local supply dynamics to shape the outcome.

What you’ll find in the collection below is a mix of on‑the‑ground reports, analysis of policy moves, and real‑world examples of how businesses and households adapt. Whether you’re a student trying to understand the basics, an investor tracking macro trends, or a policy‑maker looking for comparative insights, the articles give a clear view of the forces at play. Dive in to see how the decline in price growth is reshaping Africa’s economic landscape and what it could mean for your next purchase or investment decision.

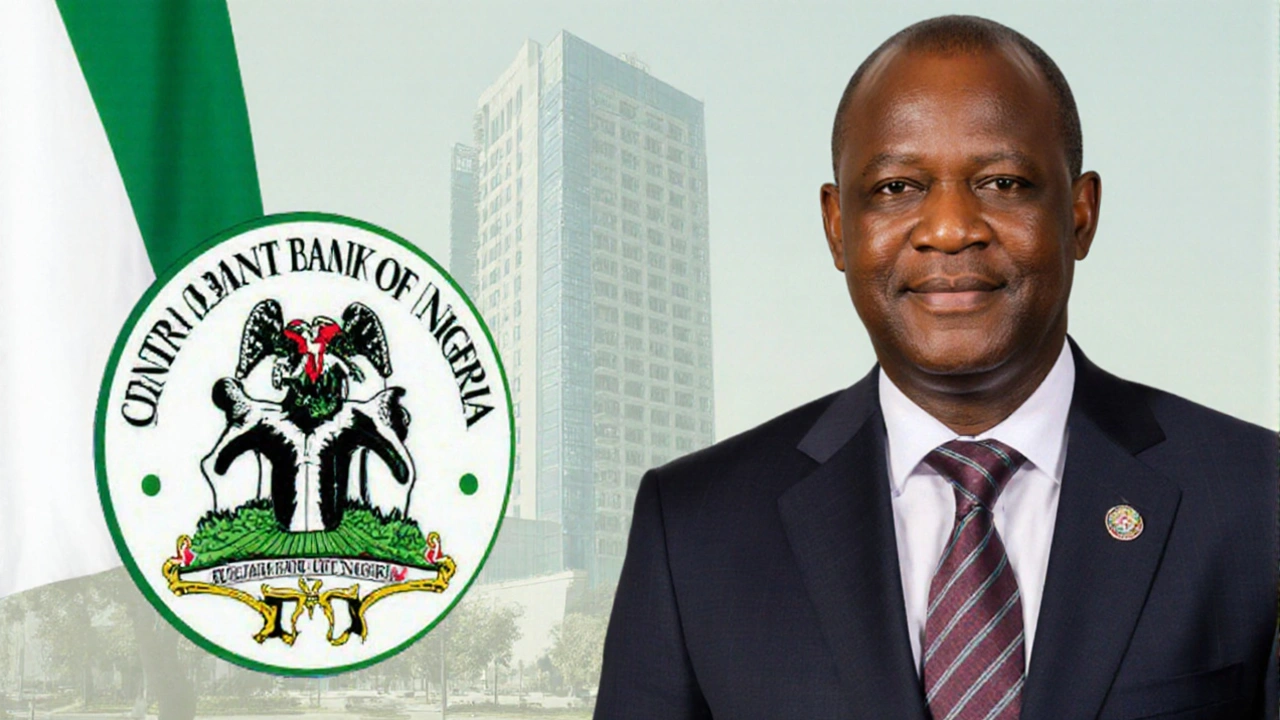

Nigeria CBN Cuts Interest Rate After Three Years, MPR Falls to 27%

At its 302nd Monetary Policy Committee meeting, the Central Bank of Nigeria lowered the Monetary Policy Rate by 50 basis points to 27%, marking the first cut in three years. The move follows five months of steady disinflation and forecasts of a continuing decline in inflation. Alongside the rate cut, the CBN tweaked the cash reserve ratio for commercial banks and introduced a higher CRR for non‑Treasury public sector deposits. Governor Yemi Cardoso chaired the session, emphasizing a balance between growth support and price stability.