Nigeria interest rate cut: What it means for the economy

When discussing Nigeria interest rate cut, the lowering of the benchmark borrowing rate by the nation's monetary authority to influence credit costs and growth. Also known as CBN rate reduction, it signals a shift in how the Central Bank approaches fiscal challenges. The Nigeria interest rate cut aims to make loans cheaper, spur spending, and ultimately boost output.

Key players and the chain of effects

At the heart of the move is Central Bank of Nigeria, the institution responsible for setting policy rates, managing inflation and safeguarding financial stability. Its decision to slash rates directly targets inflation, the rise in consumer prices that erodes purchasing power and forces tighter monetary settings. By lowering the cost of borrowing, the bank hopes to cool price pressures while encouraging businesses to invest. A secondary goal is to influence the exchange rate, the value of the naira against foreign currencies, which affects import costs and export competitiveness. In short, the Nigeria interest rate cut reduces borrowing costs (semantic triple 1), the Central Bank of Nigeria implements the cut to tame inflation (semantic triple 2), and lower rates can support exchange rate stability (semantic triple 3).

Beyond the core trio, the policy ripple touches many sectors. Monetary policy, the broader set of tools like reserve requirements and open market operations used to steer the economy becomes more accommodative, giving banks room to lower loan interest margins. GDP growth, the annual increase in the value of goods and services produced, is expected to pick up as credit expands may see a modest uptick if firms respond to cheaper finance. Savers, on the other hand, could face lower returns on deposits, prompting a shift toward higher‑yielding assets such as government bonds or real‑estate. Foreign investors, capital flows from outside Nigeria seeking returns, often watch rate moves closely because they affect risk premiums may view the cut as a sign of policy flexibility, improving the country's investment appeal.

For everyday consumers, the most visible change is in loan and mortgage payments. A reduced benchmark rate can shave points off home‑loan interest, making monthly bills more affordable. Small businesses often see lower interest on working‑capital lines, freeing cash to expand inventories or hire staff. However, the benefits depend on how quickly banks pass the rate cut through their pricing sheets. In the credit market, competition tends to increase after a cut, which can drive rates down faster. At the same time, the government may adjust fiscal measures, such as tax incentives, to complement the monetary easing.

Looking ahead, analysts keep an eye on a few warning signs. If inflation proves stubborn, the Central Bank of Nigeria could reverse course, raising rates again to avoid a loss of price stability. A sharp depreciation of the naira could offset the intended benefits of cheaper credit, especially for import‑dependent firms. Monitoring the balance between growth stimulation and inflation control will be crucial.

Below, you’ll find a curated set of articles that dive deeper into each of these angles – from the mechanics of the rate cut to its impact on borrowers, investors and the broader African financial landscape. Explore the stories to see how theory translates into real‑world outcomes across the continent.

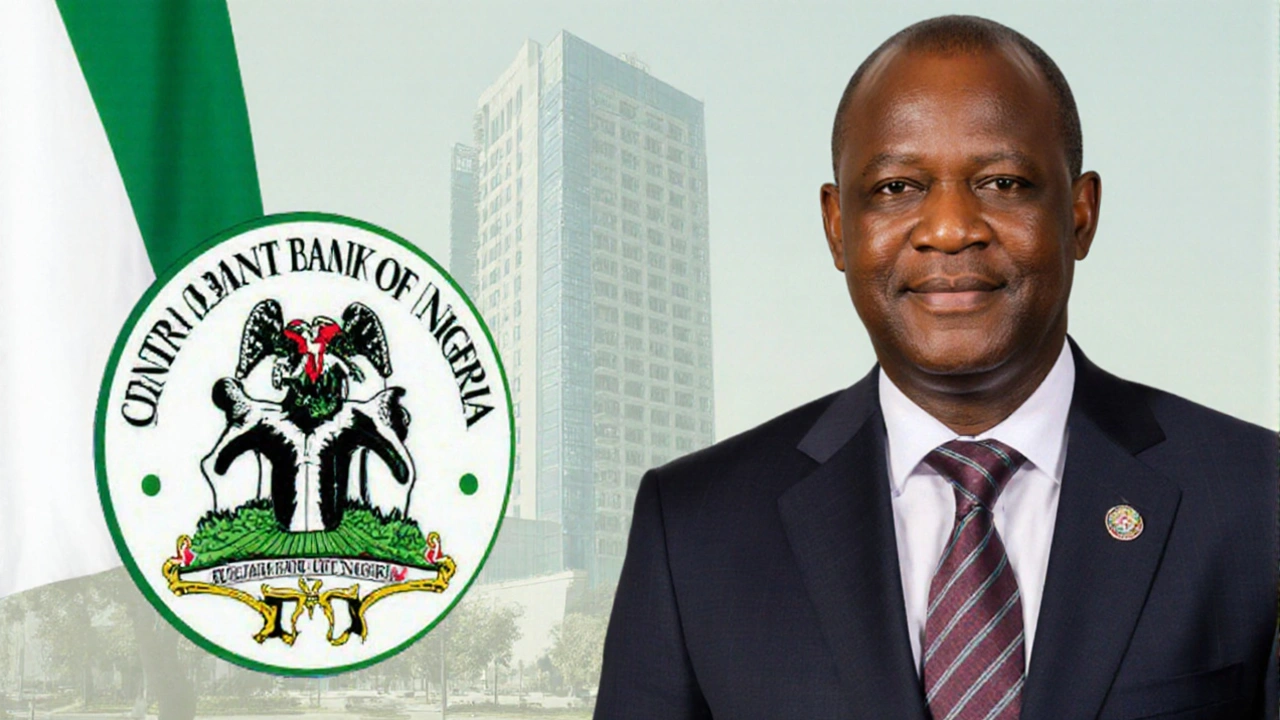

Nigeria CBN Cuts Interest Rate After Three Years, MPR Falls to 27%

At its 302nd Monetary Policy Committee meeting, the Central Bank of Nigeria lowered the Monetary Policy Rate by 50 basis points to 27%, marking the first cut in three years. The move follows five months of steady disinflation and forecasts of a continuing decline in inflation. Alongside the rate cut, the CBN tweaked the cash reserve ratio for commercial banks and introduced a higher CRR for non‑Treasury public sector deposits. Governor Yemi Cardoso chaired the session, emphasizing a balance between growth support and price stability.